The Scottish organizers served one of the most tricky World Orienteering Championships (WOC) Sprint races ever – and the Swedish duo Martin Regborn and Tove Alexandersson made the day a big Swedish success with two gold medals for Sweden. Alexandersson with her 20th WOC gold medal – Regborn with his first.

Sweden dominated the results along with Switzerland – the two nations taking home all the medals. In the men’s class Switzerland’s WOC debutant Tino Polsini took silver 23 second behind Regborn with Swedish Emil Svensk taking the bronze medal a few seconds behind. In the women’s class silver and bronze both went to Switzerland, with World Cup leader Simona Aebersold 15 seconds behind and Natalie Gemperle another 4 seconds behind.

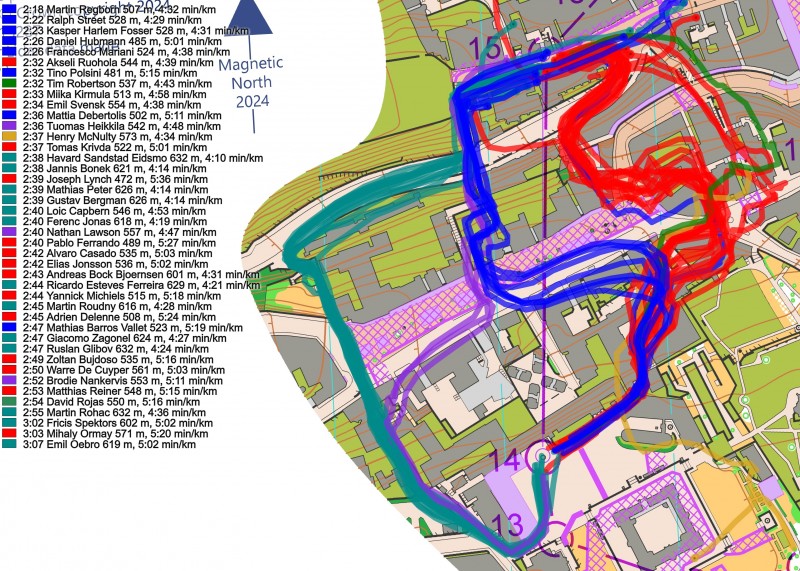

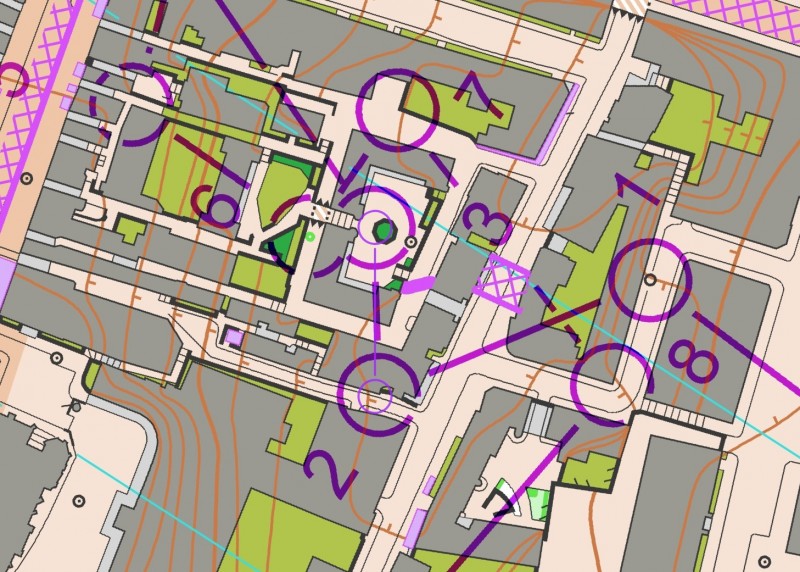

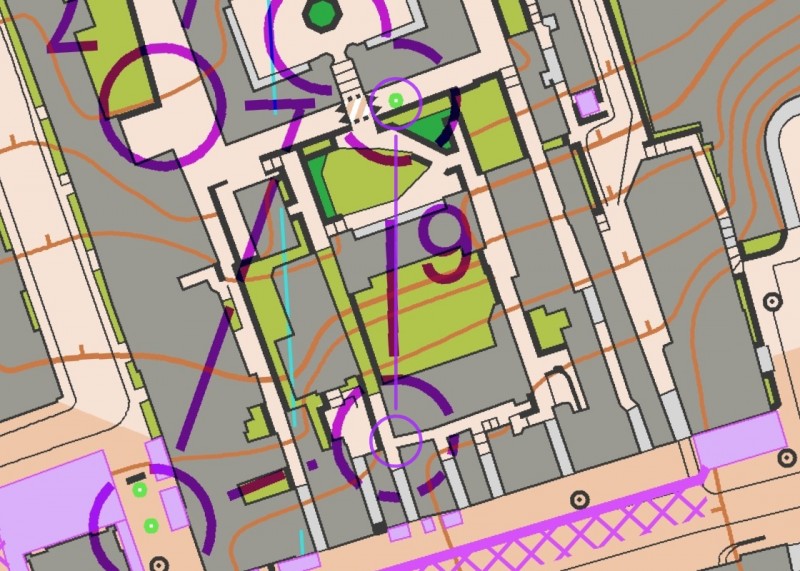

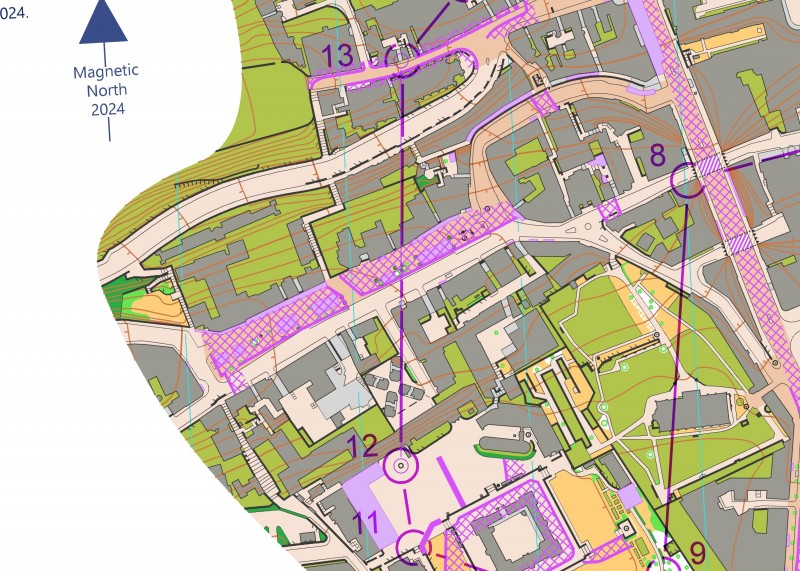

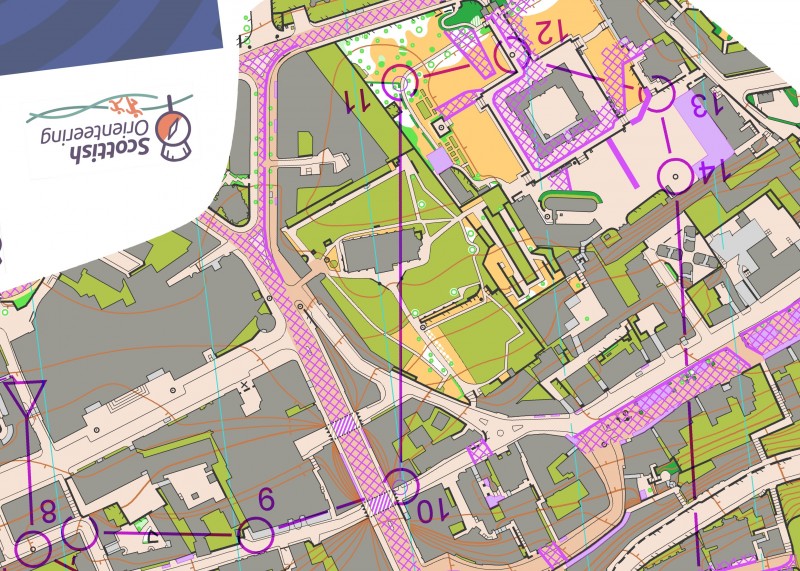

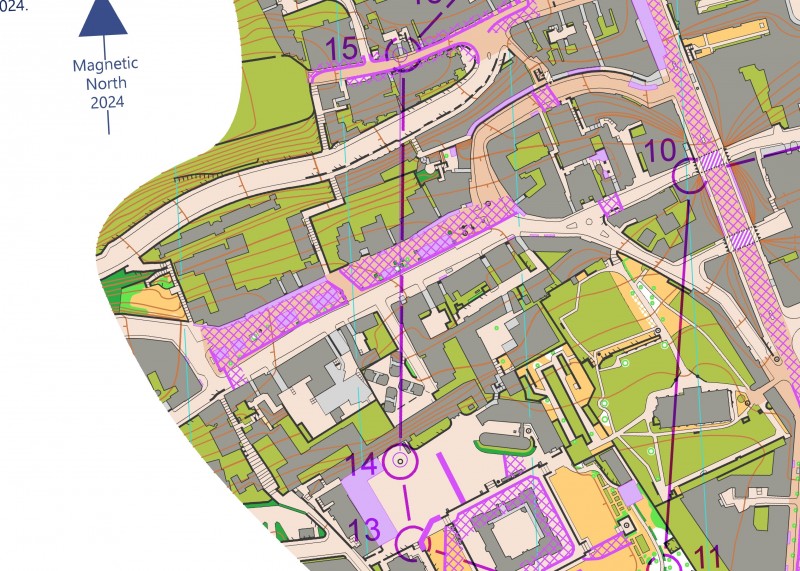

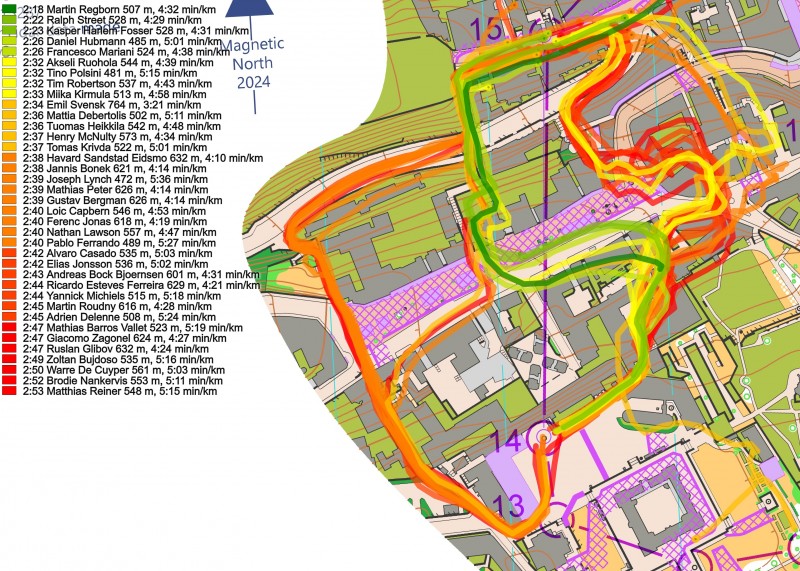

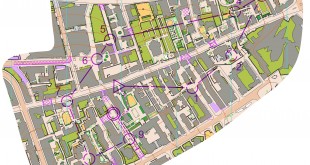

The course setters had worked extremely hard to challenge the runners, using artificial boundaries, opening up private garderns and using numerous stairs to create complex route choice puzzles for the runners. Above the 15th leg from the men’s course is shown – with very few runners finding the best route. Even if old maps of relatively good quality were available, it was difficult for the runners to prepare for all the challenges they met. After the race Alexandersson thanked the men’s winner Martin Regborn warmly for all help with preparations for the race, but also was clear on how difficult the organizers had made it for the runners.

– We had done a good job, but at the same time, the organizer had come up with some twists. There were so many tricky parts that were impossible to prepare for considering the barricades. It was really about being flexible and being able to change the plan during the race.

Other runners reported that they were just not able to see any way to get to the next control, and either “lost their head” and did some really bad choices – or used a lot of time to find a possible approach.

Below the analysis you can find maps, links to GPS-tracking and results.

Edit 13/07: This comment from one of the course setters, Graeme Ackland (thanks!), gives some additional perspectives on the analysis:

I was at various places in the area, and can report that on 2-3 almost all the top women took the (longest) green route. Sadly for home supporters, Megan Carter-Davies made a 180 degree error leaving the map exchange, losing the lead. We were well aware of the incredible detail of preparation that the athletes do for these races, but we think that the course forced them to make the key decisions during the race rather than in their armchairs. As for men 18-19 – I’m sure everyone had prepped and visualized running the route down the road but unfortunately you have to use the map you get on the day, not the one you use yourself. Another point shows how clean the sport is – the gate on the old map that Fosser and Street were headed for has been bolted shut for at least four years: it would have been easy (and cheating) for the athletes to find that out.

Men’s analysis

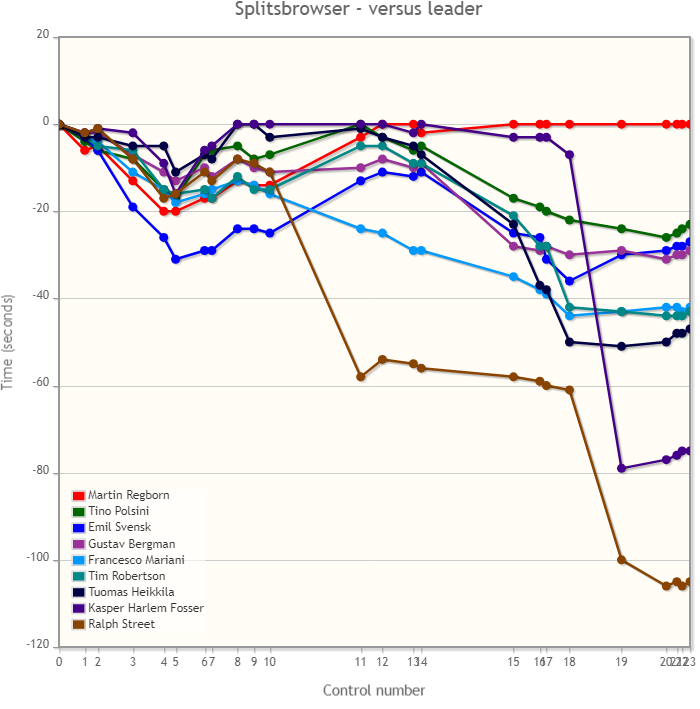

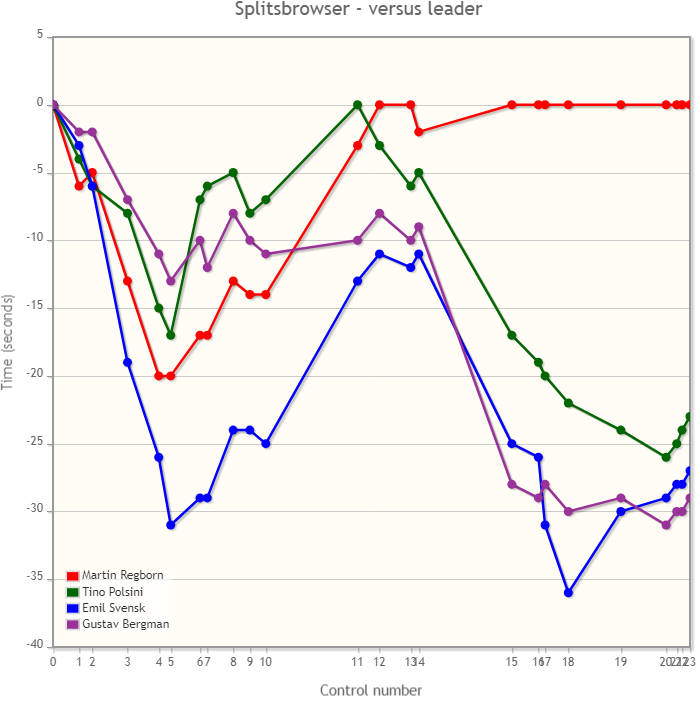

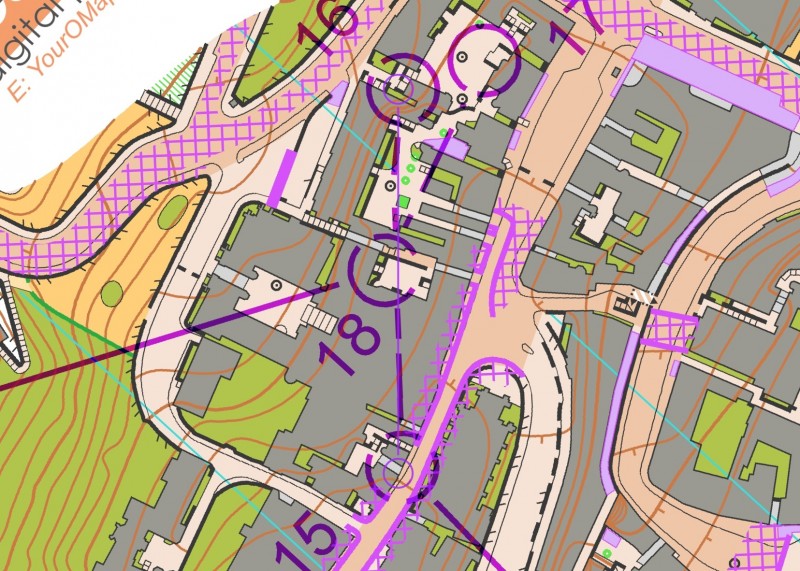

Below you can see a graphical representation of the race development in the men’s class for the Top 6 along with selected runners who performed extremely well in parts of the course.

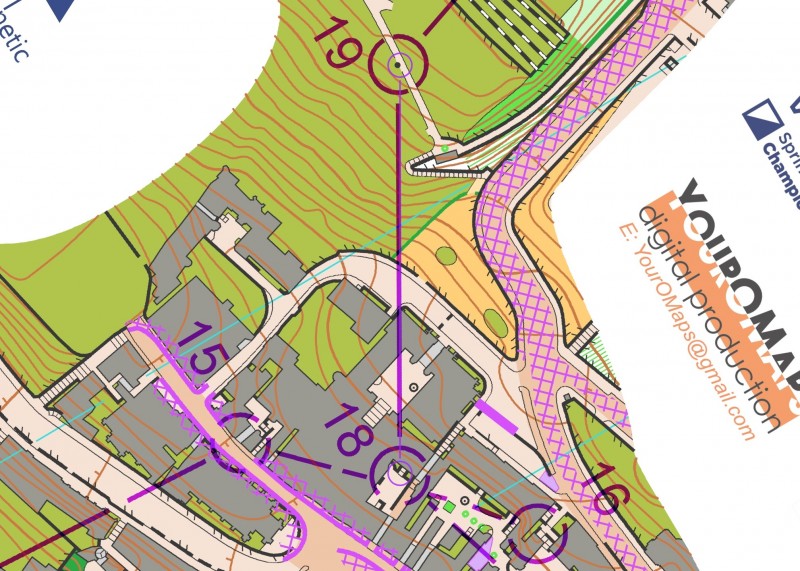

Zoltan Bujdoso was in the lead until the 8th control, but lost a lot of time at several controls and ended down in 29th place. At the 9th control Tuomas Heikkila and Kasper Fosser took over a shared lead – but none of them managed to finish the race well. Heikkila was one of the many runners losing time to control 15 (18 seconds; more detailed analysis of the leg below), and also lost major time to leg 16 and 18 – finishing down in 8th place at +47 seconds. The reigning World Champion Fosser was within a few seconds of Regborn until the 18th control, but did a major mistake to control 19 – running far into a forbidden area and having to return back the same way – losing 1:18 and finishing on a disappointing 17th place. Many other runners did the same mistake as Fosser, along with home favourite Ralph Street. Street’s race would also have been a medal race without this mistake and his other big mistake to the 11th control.

Looking at the top 4 (see separate illustration below), one can see that the main differentiator was the leg to the 15th control where Regborn is the only one of the Top 4 to take the optimal route. In addition the other Top 4 runners lost some additional seconds at a few controls; notably Emil Svensk had an exceptionally bad start, being more than 30 seconds behind the leader at the 5th control, and Gustav Bergman in 4th place lost significant time to the others to the 11th control. It is also interesting to see that all of the Top 4 where quite far behind after 5 controls.

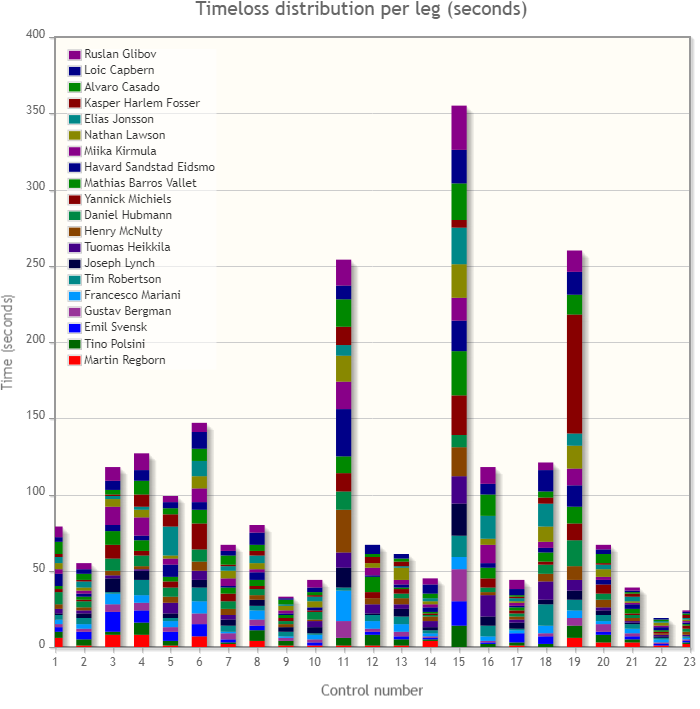

Taking a look at where the biggest time losses where for the Top 20 finishiers on this course (see illlustration below), it is clear that most time is lost to control 11, 15 and 19 – the same controls which one could pick out from looking at the race development graphs for top runners above. In addition, quite a lot of time was lost to control 3, 4, 6, 16 and 18.

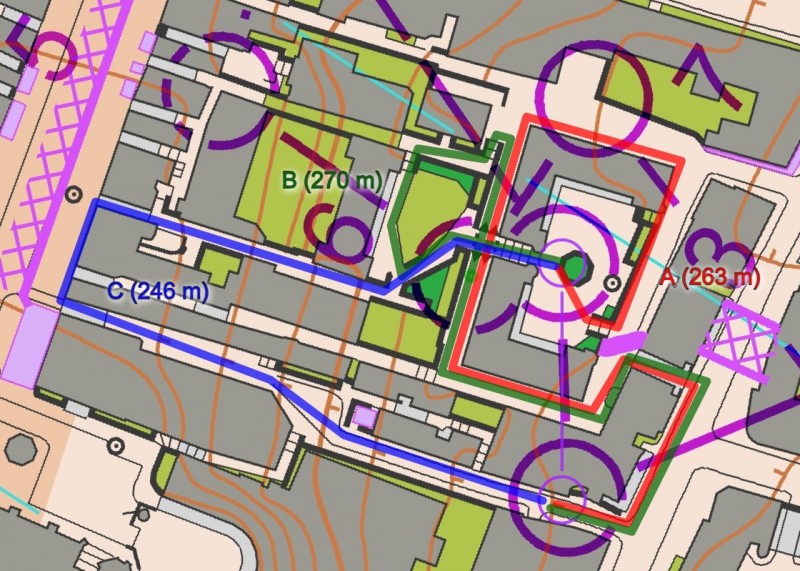

Leg analysis

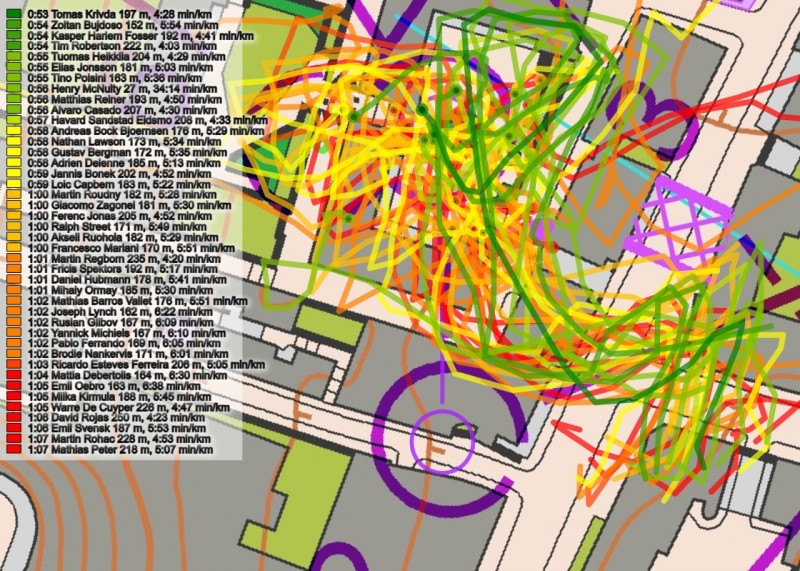

Here we take a brief look at these 8 legs. We first take a look at the legs without routes, and then we add GPS-data (with correct split times) for the longer legs where this makes sense (for the short, labyrinthic legs the GPS-data is completely unreadable)

Control 11

The leg to control 11 is a routechoice leg with two main options – one to the left and one to the right – while some run in an S (first to the right, then to the left). When executing the leg weel, both the left and right options are equal in time based on studying a combination of GPS-data and split times – with the S-variant being significantly slower. However, quite a few runners lost significant time (30-60 seconds) due to either bad execution or choosing a route which was very close to these routes – the GPS-data does not tell the complete story here, with the routes of the ones losing time being very close to the ones running fast times. But this was definitely one of the decisive legs of the day!

Control 15

This was the most decisive leg of the day, with very few runners spotting the fastest option which is a S-variant going right-left-right (blue below). While having quite a few steep staircases, this variant is short without too many 90-degree turns. Six of the seven fastest times on the leg are run on this variant – and Regborn was the only one of the Top 4 spotting this route. Is the leg too tricky when it is so difficult to spot the fastest route? On the other hand, among the 7 runners taking this route, we find Sprint World Champions Kasper Fosser, Daniel Hubmann and Martin Regborn along with World Cup winner Ralph Street and World Champs silver medalist Tino Polsini…

Control 19

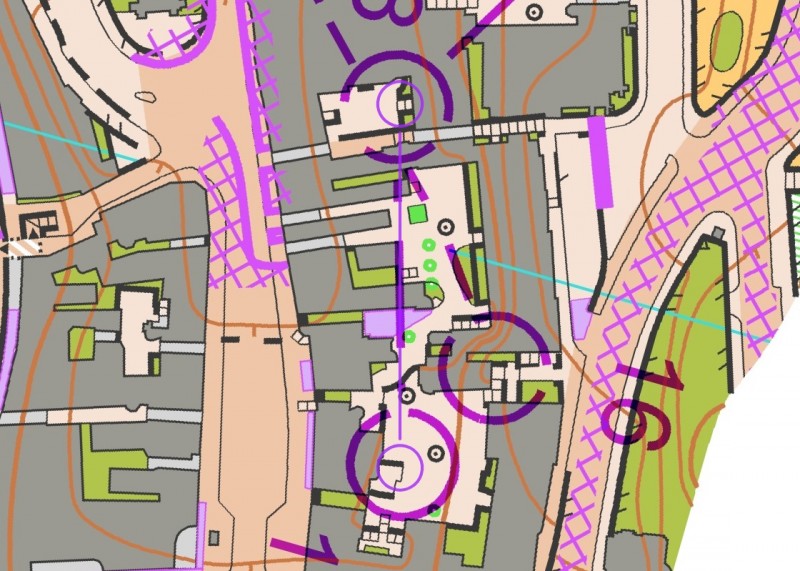

Leg 19 is the third of the legs where there were very big timelosses among the top 20 – and also where reigning World Champion Kasper Fosser lost a medal. Fosser’s issue was that he simply could not see any way to the 19th control at all (the opening into the yellow from the street is small, and the stairs between the wall and the olive green is difficult to spot), and somehow chose to run down the road into the forbidden area instead according to a comment to orientering.no. Several other runners did the same, although there may be other reasons for them running down the road than Fosser’s explanation. Again, the GPS does not tell the complete story, but the mistake of Fosser is very clearly visible here.

Control 3

For this control the GPS-data is completely garbled, so it is not really possible to see which routes the runners took and/or where they did mistakes.

This is, however, a highly interesting leg, so three different route choice options are shown below to provide some analysis of the leg (there are also other options).

Here you have to run 5 – 6 times as long as the line between the legs to get to the control! Adding the additional climb (the shortest blue route has nearly 20 meter climb which you have to run down again), this is not an easy puzzle to solve. It might seem that the red route could be the fastest, though, but with time differences being relatively modest, at least between red and green.

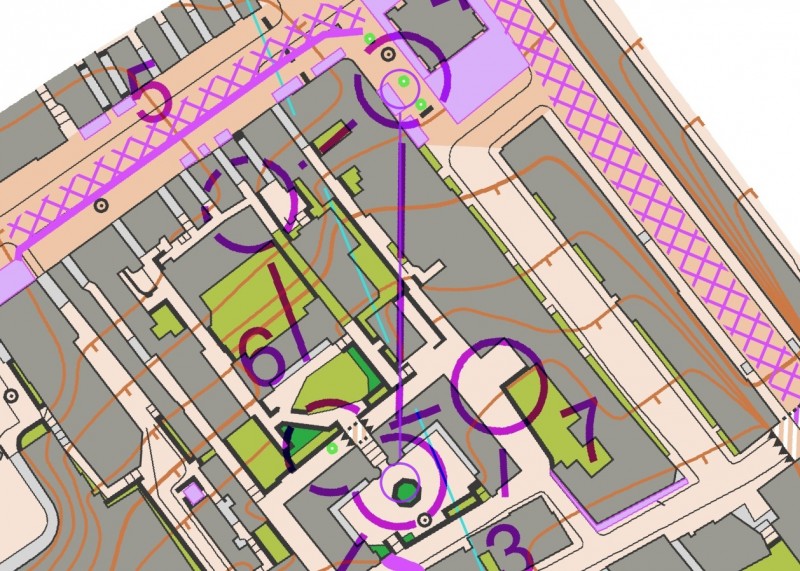

Control 4, 6, 16 and 18

For these controls the GPS-data is also completely garbled, so it is not really possible to see which routes the runners took and/or where they did mistakes. These legs are however very interesting, with complex orienteering, and are presented here without routes or detailed analysis.

Women’s analysis

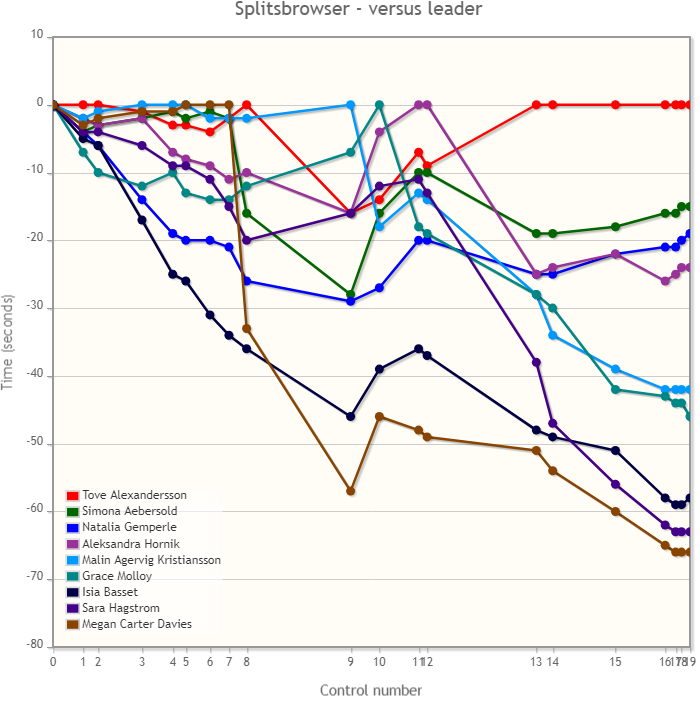

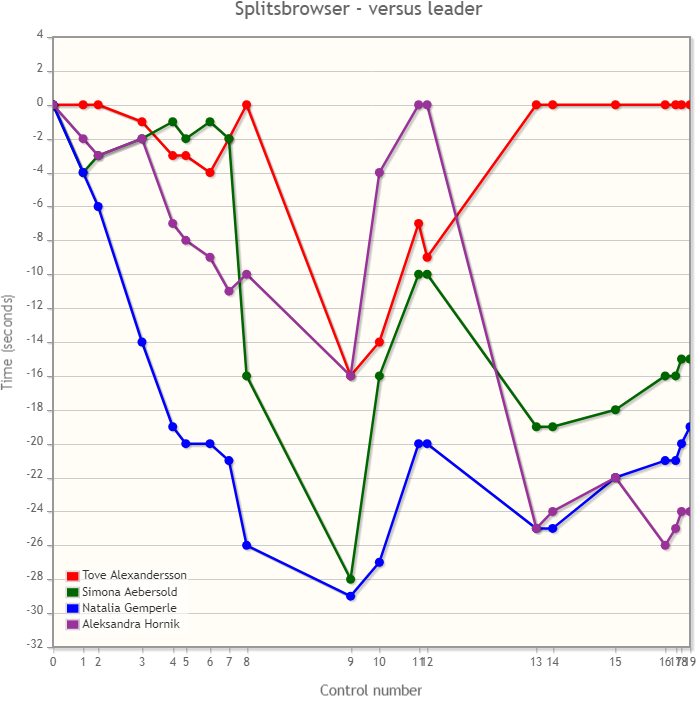

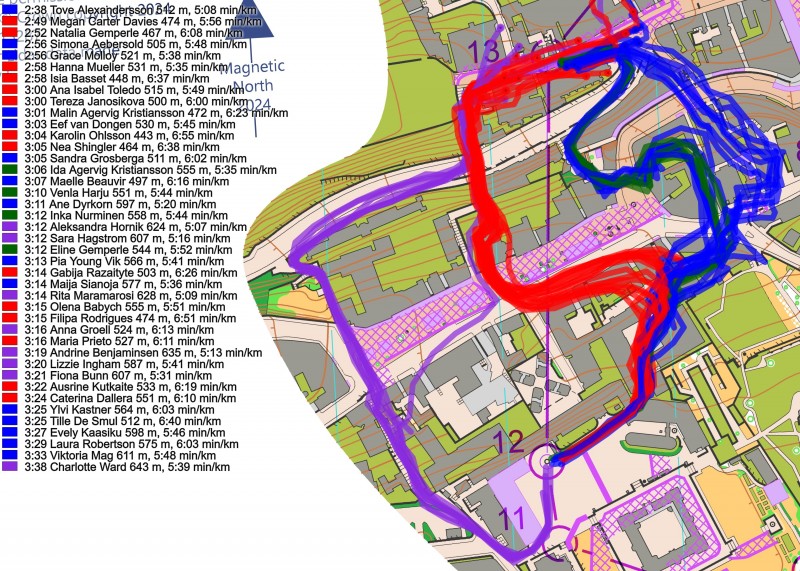

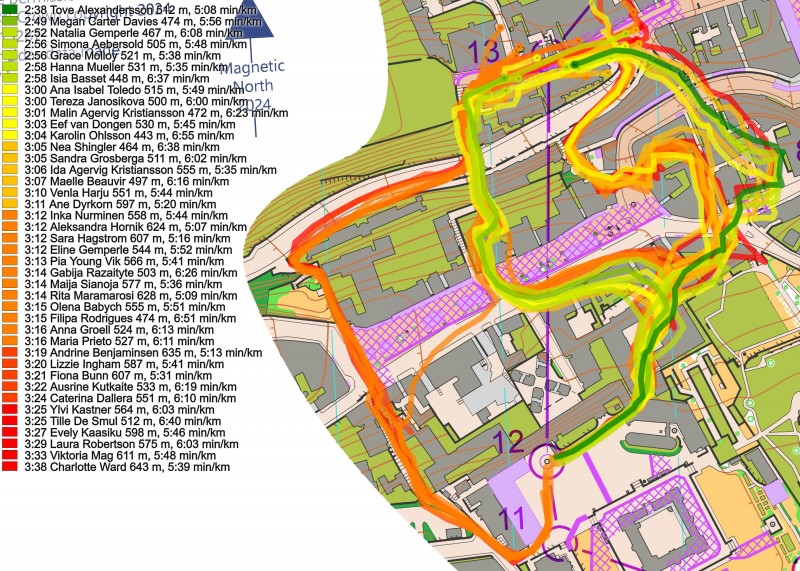

Below you can see a graphical representation of the race development in the women’s class for the Top 9.

Tove Alexandersson starts well, and is in the lead until control 2, but makes several mistakes along the way, losing the lead at control 3, taking it back at control 8, losing it again to control 9 and taking it back for the final time at control 13. Danish Malin Agervig Kristiansen (5th in the end) runs a very good race and is in the lead at control 3 and 4 – and again at control 9, but a timeloss to control 10 (which might partly have been due to an organizer mistake according to the Danish Orienteering Federation) and another one to control 13 sent her out of the medal contention. Megan Carter Davies had the lead from control 5 to control 7, but big time losses of around a minute in total to control 8 and 9 sends the reigning champion out of the medals. The home favourite, Grace Molloy, is briefly in the lead at control 10, but quite large time losses to control 11 and 13 ruin her dream day on home ground. Finally Aleksandra Hornik (Poland) had the lead on control 11 and 12 – but again control 13 was the dream crusher. Without that time loss, Hornik would actually have been up there on similar time as the queen Alexandersson!

Looking at the overall picture, the two longest legs – the leg to control 9 and the leg to control 13 – clearly seem to be the one where the biggest time differences occured. Both Aleksandra Hornik and Sara Hagström lost their medal chances on the leg to control 13 (more about that leg below in the detailed leg analysis). Tove Alexandersson and Simona Aebersold lost significant time to control 9, but their high running speed saved the medals for them.

See below for a more detailed look at the Top 4. Definitely a very impressive race by Hornik!

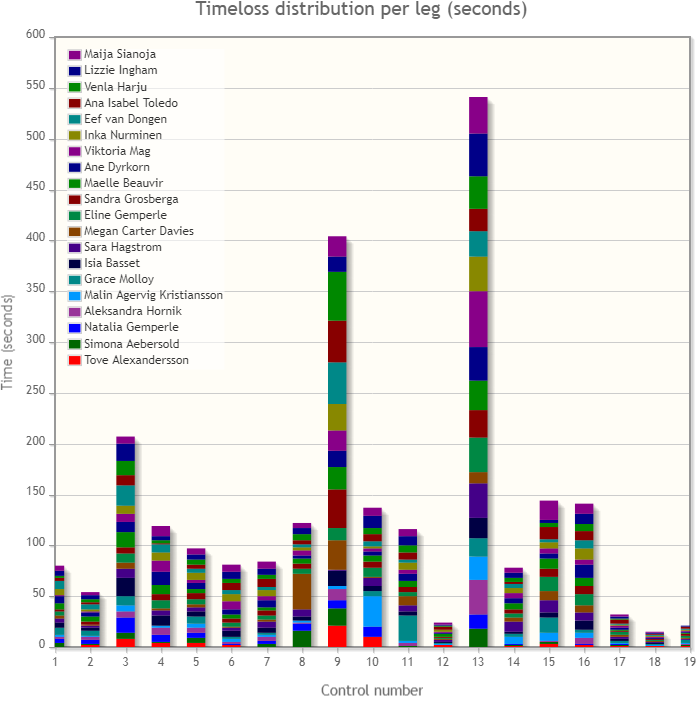

Taking a look at where the biggest time losses where for the Top 20 finishiers on this course (see illlustration below), it is clear that most time is lost to control 9 and 13 – the same controls which one could pick out from looking at the race development graphs for top runners above. In addition, quite a lot of time was lost to control 3, with the other time losses being distributed among many controls.

Leg analysis

Here we take a brief look at these 8 legs. We first take a look at the legs without routes, and then we add GPS-data (with correct split times) for the longer legs where this makes sense (for the short, labyrinthic legs the GPS-data is completely unreadable)

Control 9

The leg to control 9 is the same as the leg to control 11 in the men’s class – which was found to be decisive also for the men. In the women’s class it is also clear that left and right are quite equal, but here it is more easy to see the mistake done by several runners. The green variant below shows how several women choose a route going on the small paths in the olive green at the center of the leg, but then find out that you need to take a long detour on that route, turn around, and lose a lot of time. Alexandersson’s 20 second time loss here seems to be due to running the S-variant mentioned in the men’s analysis, but not actually running into the paths in the olive green.

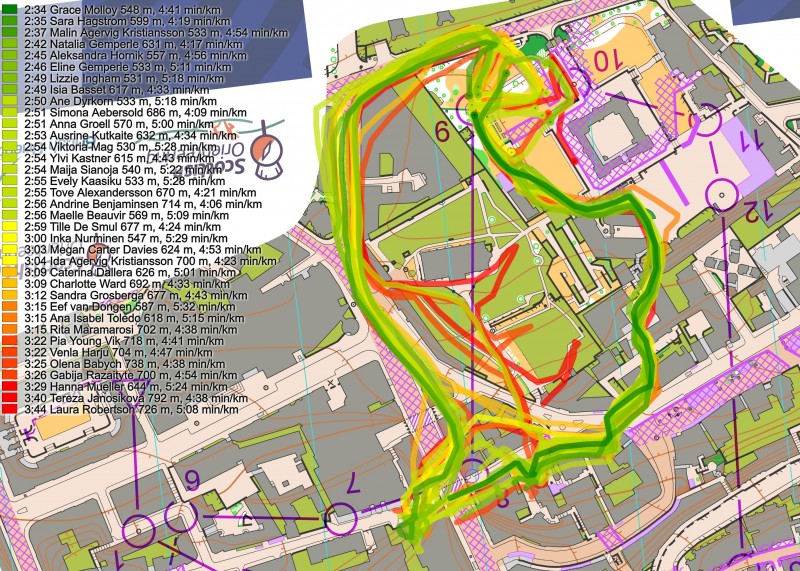

Control 13

The leg to control 13 in the women’s course is the same as the men’s leg to the 15th control. Again the S-shaped route is the fastest (except for Tove Alexandersson who can run the fastest split on nearly any route choice). Note however that a lot more women choose this fastest variant than what we see among the men.

Control 3

Control 3 (and several of the other controls) where the same as for the men – and most of these shorter legs also had completely garbled GPS.

Maps and GPS-tracking

See the map from the Men’s Sprint Final here and the map from the Women’s Sprint Final here. Links to GPS-tracking are available by clicking on the map thumbnails below.

Final

WOC 2024 | Sprint Final | Men

» See map in omaps.worldofo.com

WOC 2024 | Sprint Final | Women

» See map in omaps.worldofo.com

Qualification

WOC 2024 | Sprint Q | Men heat 1

» See map in omaps.worldofo.com

WOC 2024 | Sprint Q | Men heat 3

» See map in omaps.worldofo.com

WOC 2024 | Sprint Q | Women heat 2

» See map in omaps.worldofo.com

WOC 2024 | Sprint Q | Women heat 1

» See map in omaps.worldofo.com

WOC 2024 | Sprint Q | Men heat 2

» See map in omaps.worldofo.com

Results

Men Final

| 1 | Martin Regborn | 15:58 | 3:38 | |||

| 2 | Tino Polsini | 16:21 | +0:23 | 3:44 | ||

| 3 | Emil Svensk | 16:25 | +0:27 | 3:45 | ||

| 4 | Gustav Bergman | 16:27 | +0:29 | 3:45 | ||

| 5 | Francesco Mariani | 16:40 | +0:42 | 3:48 | ||

| 6 | Tim Robertson | 16:41 | +0:43 | 3:48 | ||

| 7 | Joseph Lynch | 16:44 | +0:46 | 3:49 | ||

| 8 | Tuomas Heikkila | 16:45 | +0:47 | 3:49 | ||

| 9 | Henry McNulty | 16:52 | +0:54 | 3:51 | ||

| 10 | Daniel Hubmann | 16:53 | +0:55 | 3:51 | ||

| 11 | Yannick Michiels | 16:59 | +1:01 | 3:52 | ||

| 12 | Mathias Barros Vallet | 17:01 | +1:03 | 3:53 | ||

| 13 | Havard Sandstad Eidsmo | 17:02 | +1:04 | 3:53 | ||

| 14 | Miika Kirmula | 17:04 | +1:06 | 3:54 | ||

| 15 | Nathan Lawson | 17:09 | +1:11 | 3:55 | ||

| 16 | Elias Jonsson | 17:11 | +1:13 | 3:55 | ||

| 17 | Kasper Harlem Fosser | 17:13 | +1:15 | 3:56 | ||

| 18 | Loic Capbern | 17:17 | +1:19 | 3:57 | ||

| 18 | Alvaro Casado | 17:17 | +1:19 | 3:57 | ||

| 20 | Ruslan Glibov | 17:24 | +1:26 | 3:58 |

Women Final

| 1 | Tove Alexandersson | 16:14 | 4:14 | |||

| 2 | Simona Aebersold | 16:29 | +0:15 | 4:18 | ||

| 3 | Natalia Gemperle | 16:33 | +0:19 | 4:19 | ||

| 4 | Aleksandra Hornik | 16:38 | +0:24 | 4:20 | ||

| 5 | Malin Agervig Kristiansson | 16:56 | +0:42 | 4:25 | ||

| 6 | Grace Molloy | 17:00 | +0:46 | 4:26 | ||

| 7 | Isia Basset | 17:12 | +0:58 | 4:29 | ||

| 8 | Sara Hagstrom | 17:17 | +1:03 | 4:31 | ||

| 9 | Megan Carter Davies | 17:20 | +1:06 | 4:31 | ||

| 10 | Eline Gemperle | 17:26 | +1:12 | 4:33 | ||

| 11 | Sandra Grosberga | 17:30 | +1:16 | 4:34 | ||

| 12 | Ane Dyrkorn | 17:35 | +1:21 | 4:35 | ||

| 12 | Maelle Beauvir | 17:35 | +1:21 | 4:35 | ||

| 12 | Inka Nurminen | 17:35 | +1:21 | 4:35 | ||

| 12 | Viktoria Mag | 17:35 | +1:21 | 4:35 | ||

| 16 | Eef van Dongen | 17:39 | +1:25 | 4:36 | ||

| 17 | Ana Isabel Toledo | 17:41 | +1:27 | 4:37 | ||

| 18 | Venla Harju | 17:43 | +1:29 | 4:37 | ||

| 19 | Lizzie Ingham | 17:47 | +1:33 | 4:38 | ||

| 20 | Maija Sianoja | 17:52 | +1:38 | 4:40 |

World of O News

World of O News

It would be nice to also mention countries outside of the two big favourites….there were an impressive 3 Oceania men in the Top 10. Tim Robertson in 6th, Joseph Lynch in 7th and Henry McNulty in 9th.

Definitely, Bob! Also a great result by Italian Mariani in 5th place. And lots of other great performances by the “smaller” orienteering nations, really nice to see. So much more could have been written about this race, but unfortunately the night hasn’t got enough hours for it :-)

Fun fact – the first 13 starters on the women’s final were all from different countries!

Thanks for the nice analysis. I was at various places in the area, and can report that on 2-3 almost all the top women took the (longest) green route. Sadly for home supporters, Megan Carter-Davies made a 180 degree error leaving the map exchange, losing the lead. We were well aware of the incredible detail of preparation that the athletes do for these races, but we think that the course forced them to make the key decisions during the race rather than in their armchairs. As for men 18-19 – I’m sure everyone had prepped and visualized running the route down the road but unfortunately you have to use the map you get on the day, not the one you use yourself. Another point shows how clean the sport is – the gate on the old map that Fosser and Street were headed for has been bolted shut for at least four years: it would have been easy (and cheating) for the athletes to find that out. We go again tomorrow in the Sprint Relay with very different terrain.

Thanks a lot for the insights, Graeme, highly appreciated!

Thanks for the analysis Jan and the comments Graeme.

If Kasper’s GPS trace is correct (and from his (reported) comments it appears to be) then shouldn’t he be disqualified for entering a forbidden area ? I note he is still in the official results.

No, according to ‘Lex-Daniel Hubmann’

Not if you ‘re-enter’ the forbidden area and have no advantage. Like NOR/SUI/FIN/CZE’ did at the relay in Kolding, WOC2022.

KH/Søren

Rule Book:

A competitor who breaks any rule, or who benefits from the breaking of any rule, may be sanctioned.

The sanctions that may be applied are:

• A time penalty for jumping the start in a mass start format race

• Disqualification

• Suspension from competition for a defined period (only by the IOF Disciplinary Panel)

the important point here is **may** :-)

No, it is well established championship precedence for this: If you enter an OOB area, realize this and then return the same way to get out of the OOB in the same spot, then there is no added penalty besides the time lost on the mistake.

BTW, the ‘may’ in that regulation can be traced back around 40 years, to the time when my father Hans Mathisen was the chairman (as it was called at the time) of the rules and regulations committee of the Norwegian Orienteering Federation. At this time Sweden was arguing for extremely strict regulations (which they enacted in Sweden) so that there would be absolutely no leniency possible:

Break any rule ->> automatic DSQ.

Thankfully on the international level, Sweden was down-voted, so that the organizers and jury were given enough leeway to accept any accidental mistakes that had not gained any time.

Good work, appreciated!

When do you think we can have some technology that would replace GPS in sprint races? Is there any talk about dedicated networks or drones following the individual runners? Thinking that there has to be technology available, but maybe still too expensive…

Thanks for analysis. Any chances to include also Hanna Lundberg?

Thanks SirN and Dr. Phil.

The wording in that clause gives the jury a huge amount of discretion as to whether to apply a penalty and if so what that penalty should be. I guess it’s good to have flexibility, which allows for common sense penalties to be (or not be) applied. But it creates a risk of inconsistent application within and between races. Which juries might try to avoid by just going back to previous cases and using them as a precedent (kinda like the US Supreme Court trying to interpret and apply the Constitution). Anyway, I’m sure smarter minds than me at the IOF have thought this all through.

See my other response: Both precedence and common sense can and have been applied several times!

Thanks for the great analysis.

Make a mistake

Make a mistake

Make a mistake

Never: ‘do’ a mistake.

So simple to learn this small bit of English grammar! Why not try! It will put you ahead of 90% of others.

Sorry, I did a mistake, I will try to improve!

“But it creates a risk of inconsistent application within and between races” Races themselves are inconsistent. The natural world is inconsistent. Trying to write a rule that covers everything that might possibly be encountered leads to the sort of stupid strict rules that results in “computer says no” types of unreasonable destruction of peoples enjoyment and months of preparation. To take just one instance – the disqualification of a competitor in a previous world championships at the last control that many spectators and a camera saw her punch.

Did they really see her punch or did they see her trying to punch though?

The TV coverage shows two runners punching together, the DQed runner at the further away unit, which nobody running alone would ever use. You can see her holding in the SI card for longer than the other runner. By far the most likely explanation is that that unit wasn’t woken up.

On the OOB, “may” is the crucial and sensible word. It gives the organiser flexibility to be sensible. We wouldn’t want to DQ someone for stepping on some grass to avoid colliding with a member of the public. Interestingly, in the 2014 race, Daniel Hubmann ducked under the crossible fence and jumped down the “uncrossible” wall east of where #19 is. Its about 3m high at one end, 1m high at the other. He would have won by a handy margin, and nobody saw him, but he insisted on being disqualified.